In cuttings, adventitious roots can be regenerated from detached or wounded plant organs, and this process is known as de novo root regeneration. In

Arabidopsis thaliana leaf cuttings (Liu et al.

2014; Xu

2018), detached

A. thaliana leaves are responsive to wound signals and many environmental stimuli, and then synthesize a certain level of auxin, which is transported to regeneration-competent cells (i.e., procambium and some vascular parenchyma cells near the wound site) to promote cell fate transitions for adventitious root organogenesis (Xu

2018). Auxin is the key hormone mediating the cell fate transitions from regeneration-competent cells to adventitious root apical meristem (adRAM) cells. In the first step of cell fate transition (i.e., priming), the auxin signaling pathway promotes the expression of

WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX11 and

12 (

WOX11/

12), which lead to the conversion of regeneration-competent cells to adventitious root founder cells (Liu et al.

2014). In the second step (i.e., initiation), WOX11/12 and the auxin signaling pathway induce the expression of

LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN16 (

LBD16),

WOX5/

7, and

RGF1 INSENSITIVE1/

2 (

RGI1/

2), which facilitate the transition of adventitious root founder cells to adventitious root primordium (adRP) cells via cell division (Liu et al.

2014; Zhang et al.

2023). In the third step (i.e., patterning), the adRP cells divide continuously with the patterning of different tissue domains to form the adRAM. A previous study that examined adventitious rooting from hypocotyls indicated that cytokinin might influence the patterning of the adRAM (Della Rovere et al.

2013). In the fourth step (i.e., emergence), the mature adventitious root tip is formed and grows out of the leaf explant. Although the role of auxin in this process has been extensively studied, our knowledge of the contribution of cytokinin to de novo root regeneration is still limited. In this study, we revealed that cytokinin is required for the patterning step that determines the tissue differentiation of the adRAM.

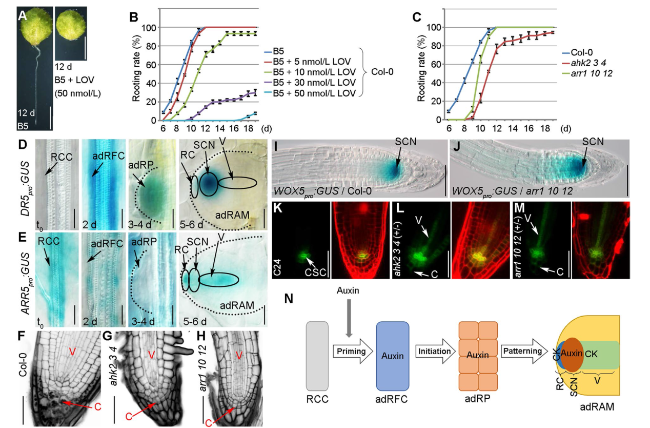

We first analyzed the role of cytokinin in adventitious rooting from detached

A. thaliana leaves. Briefly,

A. thaliana seedlings were grown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium at 22 °C with a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle. The first rosette leaf pair was cut from 12-day-old seedlings and cultured on B5 medium (Gamborg B5 basal medium with 0.5 g/L MES, 3% sucrose, and 0.8% agar, pH 5.7) to regenerate adventitious roots in darkness. Treating the detached leaves with the cytokinin biosynthesis inhibitor lovastatin (LOV) (Crowell & Salaz

1992) adversely affected rooting (

Fig. 1A,

B). Mutations in the cytokinin receptor-encoding

ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE (

AHK) genes (i.e., in the

ahk2-2 ahk3-3 ahk4-1 triple mutant) (Higuchi et al.

2004) or the cytokinin signaling-related transcription factor-encoding B-type

ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR (

ARR) genes (i.e., in the

arr1-3 arr10-5 arr12-1 triple mutant) (Mason et al.

2005) resulted in the partially defective regeneration of adventitious roots from detached leaves (Bustillo-Avendaño et al.

2018) (

Fig. 1C). Accordingly, cytokinin is likely involved in the adventitious rooting from detached leaves.

We next examined auxin and cytokinin patterns during adventitious root organogenesis. In the auxin marker line transformed with

DR5pro:GUS (Ulmasov et al.

1997), the GUS signal was almost undetectable in the regeneration-competent cells at time 0 (t

0), whereas it was relatively strong in the adventitious root founder cells at approximately 2 days after the leaves were detached as well as in the adRP at approximately 3 to 4 days after the leaves were detached (

Fig. 1D). Notably, in the adRAM, the signal was restricted to the stem cell niche and was absent in the root cap and vascular regions at approximately 5 to 6 days after the leaves were detached (

Fig. 1D). In addition, LOV treatment could cause the ectopic GUS signal in the root cap region of the adRAM (Supplementary Fig. S1A).

The cytokinin signaling reporter line

ARR5pro:GUS was produced by amplifying an approximately 1.6 kb

ARR5 promoter sequence via PCR using the primers 5′-GCCAAGCTTGGAAACCAATAAAGCATATTTG-3′ and 5′-GCTGTCGACATCAAGAAGAGTAGGATCGTGAC-3′, inserting it into pBI101, and transformation of the construct into Col-0. The

ARR5pro:GUS and

DR5pro:GUS constructs had antagonistic expression patterns, with

ARR5pro:GUS expressed at a relatively high level in the regeneration-competent cells and at an undetectable level in the adventitious root founder cells and the adRP (

Fig. 1E). In the adRAM, it was expressed in the root cap and vascular regions but not in the stem cell niche (

Fig. 1E). In addition, LOV treatment could lead to the reduced GUS signal in the adRAM (Supplementary Fig. S1B).

The auxin and cytokinin marker lines indicate that auxin and cytokinin likely function antagonistically in different steps and cells during the cell fate transition and cell differentiation associated with adventitious root organogenesis. Briefly, the adventitious root founder cells and the adRP contain a high level of auxin and an undetectable level of cytokinin. In the adRAM, auxin is accumulated in the stem cell niche region, whereas cytokinin is accumulated in the root cap and vasculature.

A modified pseudo-Schiff propidium iodide (mPS-PI) staining method (Truernit et al.

2008; Pi et al.

2015) was used to analyze the newly formed adventitious root tip. The comparison with the wild-type Col-0 revealed defects in cell division and starch grain accumulation in the columella of the root cap as well as an abnormally organized vasculature and ground tissue in

ahk2-2 ahk3-3 ahk4-1 and

arr1-3 arr10-5 arr12-1 (

Fig. 1F-H). The stem cell niche marker

WOX5pro:GUS (Sarkar et al.

2007; Liu et al.

2014) was expressed in a wider region of the adventitious root tip in

arr1-3 arr10-5 arr12-1 than in Col-0 (

Fig. 1I,

J). The columella stem cell marker J2341 (C24 genetic background) (Pi et al.

2015) was more extensively expressed in the stem cell niche in

ahk2-2 ahk3-3 ahk4-1 (+ / −) and

arr1-3 arr10-5 arr12-1 (+ / −) than in the wild-type C24 (

Fig. 1K-M). Furthermore, it was ectopically expressed in the vascular regions and columella of the two mutants, but not in C24 (

Fig. 1K-M). These observations suggest that the stem cell niche identity is ectopically maintained in the root cap and the vascular cells if the cytokinin signaling pathway is defective.

In conclusion, the cytokinin signaling pathway contributes to the tissue patterning during the adRP-to-adRAM transition (

Fig. 1N). The adRP may be a primitive form of the stem cell niche controlled by a high auxin level (Xu

2018). During the transition from the adRP to the adRAM, the cells in some domains gradually differentiate into functional tissues and eliminate the stem cell niche identity. Cytokinin may be involved in the elimination of the stem cell niche identity and tissue differentiation in those domains via its antagonistic effects on auxin, thereby ensuring the maturation of the adRAM.