Introduction

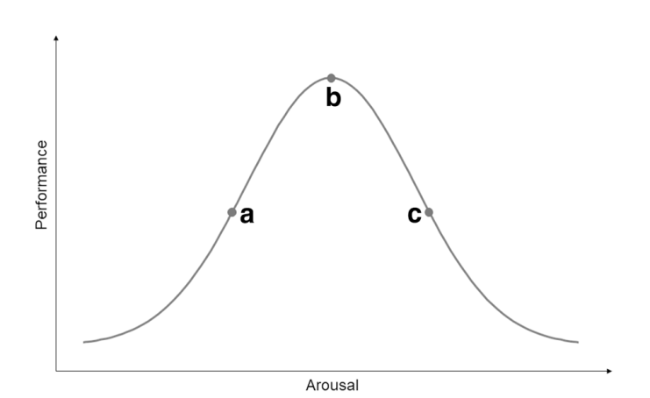

Fig. 1 The relationship between arousal and task performance, related to the effects of compensatory strategies targeting arousal. Based on Yerkes and Dodson [25]. (a) Suboptimal state of arousal. In the case of suboptimal arousal, a person with Parkinson’s disease (PD) would likely benefit from applying a compensation strategy that aims to increase the level of arousal (e.g., by adding an element of time pressure), in order to optimize task performance. (b) Optimal state of arousal. In the case of optimal arousal, optimal task performance is expected. (c) Supraoptimal state of arousal. In the case of supraoptimal arousal, a person with PD would likely benefit from applying a compensation strategy that aims to reduce the level of arousal (e.g., by employing relaxation techniques), in order to optimize task performance |

Methods

Study population

Survey

Data processing and analysis

Ethical approval

Results

Study population

Table 1 Respondent characteristics |

| Total cohort | Have used ‘Altering the Mental State’ strategies | Have never used ‘altering the mental state’ strategies | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents (n (%)) | 4324 | 1343 (31.1) | 2981 (68.9) | |

| Men (n (%)) | 2387 (55.3) | 706 (52.6) | 1681 (56.4) | 0.022* |

| Age (years) | 67.8 ± 9.0 | 67.5 ± 9.0 | 68.6 ± 9.0 | 0.371 |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 6.7 ± 5.3 | 7.0 ± 5.3 | 6.5 ± 5.2 | 0.004* |

| Respondents with FOG (n (%)) | 1900 (43.9) | 661 (49.2) | 1239 (41.6) | < 0.001* |

| NFOG-Q scorea (median [range]) | 17 [1-28] | 18 [1-27] | 17 [1-28] | 0.005* |

| Experienced ≥ 1 fall in preceding 12 months (n (%)) | 2266 (52.4) | 784 (58.4) | 1482 (49.7) | < 0.001* |

Values are presented as mean ± SD, unless otherwise specified FOG, Freezing of gait; NFOG-Q, New Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (score range 0-28) [29] The asterisks indicates that the presented p-value has surpassed the threshold of statistical significance (<0.05) aAmong respondents with freezing of gait, defined by a non-zero NFOG-Q score bRespondents who had ever used ‘Altering the Mental State’ strategies versus Respondents who had never used ‘Altering the mental State’ strategies, assessed by independent t-tests and chi-square tests *Statistically significant difference |

‘Altering the Mental State’ strategies

Table 2 Reported ‘Altering the Mental State’ strategies for gait impairments in Parkinson’s disease |

| Principle mechanism | Phenomenology | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reducing arousal | Facilitating general relaxation | Mindfulness Breathing techniques Meditation Yoga Qigong Tai chi Self-hypnosis Spirituality Low-intensity physical exercise* Doing something one loves Being on holiday Being somewhere one loves Listening to one’s favourite music Taking anxiolytic drugs, or medicinal cannabis |

| Eliminating negative emotions and cognitions surrounding gait | Focussing on what you CAN do Rationalize stressful events Consciously stop worrying Thinking about one’s most positive experiences Using mantra’s, or positive affirmations Visualizing a successful situation Taking antidepressants | |

| Decreasing external (social) pressure | Avoiding feeling rushed by other persons Communicating beforehand how one is feeling, so people can take it into account Pretending to be the only person around | |

| Having a back-up plan in case of gait difficulties | Carefully planning out the walk beforehand ‘Crisis rehearsal’ of bottleneck areas of the route beforehand Walking a ‘test round’ indoors before heading outside Wearing laser shoes, without having to look at the projections Holding a cane, without using it for support Having someone close by | |

| Increasing arousal | Internal factors | Getting angry at oneself and using that energy to walk Inflicting pain on oneself Getting ‘pumped’ through forceful self-talk or high-intensity physical exercise* Purposefully creating a time-pressure situation Pretending to be on stage, ready to perform in front of a large audience Challenging oneself to make each step better than the one before |

| External factors | Being in ‘test’ situations, such as at the doctor’s office Being in an emergency, or otherwise thrilling situation |

*While low-intensity exercise is typically applied to facilitate general relaxation (i.e., decrease arousal), some persons employ higher intensity physical exercise to ‘get pumped’ (i.e., increase arousal) |

Strategies that reduce arousal

Strategies that increase arousal

Subgroup characterization

Table 3 Subgroup characteristics |

| Have used strategies that reduce arousal | Have used strategies that increase arousal | Have used both types of strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents (n (%))a | 1122 (83.5) | 92 (6.9) | 98 (7.3) |

| Men (n (%)) | 588 (52.6) | 60 (65.2) | 43 (43.9) |

| Age (years) | 67.4 ± 9.0 | 68.7 ± 8.6 | 67.8 ± 9.1 |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 7.0 ± 5.4 | 7.1 ± 5.1 | 6.3 ± 4.9 |

| Respondents with FOG (n (%)) | 553 (43.9) | 54 (58.7) | 44 (44.9) |

| NFOG-Q scoreb (median [range]) | 18 [1-27] | 17 [5-25] | 17 [1-24] |

| Experienced ≥ 1 fall in preceding 12 months (n (%)) | 656 (58.5) | 51 (55.4) | 53 (60.2) |

Values are presented as mean ± SD, unless otherwise specified FOG, Freezing of gait; NFOG-Q, New Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (score range 0-28) [29] aOf respondents who had ever tried ‘Altering the Mental State’ strategies. NB: 31 respondents (2.3%) did not specify what kind of mental state strategy they had ever used bAmong respondents with freezing of gait, defined by a non-zero NFOG-Q score |

Discussion

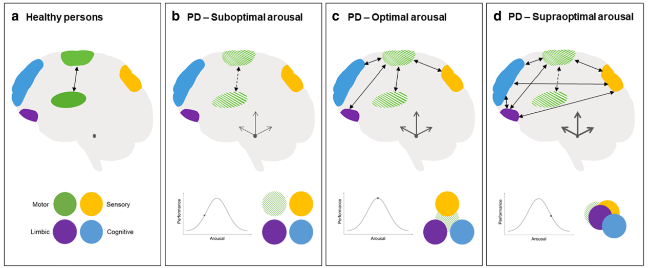

Fig. 2 How modulating arousal may contribute to optimal gait performance in Parkinson’s disease (PD). a Healthy persons. In healthy persons, the primary automatic mode of motor control is intact. Different brain networks are largely segregated, as there is (usually) no need for compensatory input to achieve optimal gait control. b PD—Suboptimal arousal. Impaired function of the corticostriatal motor network cannot be optimally compensated for by complementary input from other brain networks, as these networks remain largely segregated in this suboptimal state of arousal. c PD—Optimal arousal. Impaired function of the corticostriatal motor network can be optimally compensated for by complementary input from other brain networks, as these networks are optimally integrated in this optimal state of arousal. d PD—Supraoptimal arousal. Impaired function of the corticostriatal motor network cannot be optimally compensated for by complementary—but now competing—input from other brain networks, as these networks are engaged in dysfunctionally increased ‘cross-talk’ in this supraoptimal state of arousal. Green circle: intact corticostriatal motor network; Dashed green circle: impaired corticostriatal motor network; Yellow circle: sensory network; Purple circle: limbic network; Blue circle; cognitive network. Black double-sided triangle arrows represent a simplified schematic illustration of the functional integration between the different brain regions (which is presumably much more complex than depicted); Dashed arrows indicate the impaired function of the primary motor circuitry in PD; Thickness of the dark-grey equilateral barb arrows represents the neuromodulatory activity of the locus coeruleus (depicted here in the rostral pons as a small dark-grey ellipse). Figure inspired by Gilat et al. [48] |